28 Introduction

28.1 The multiplicity problem

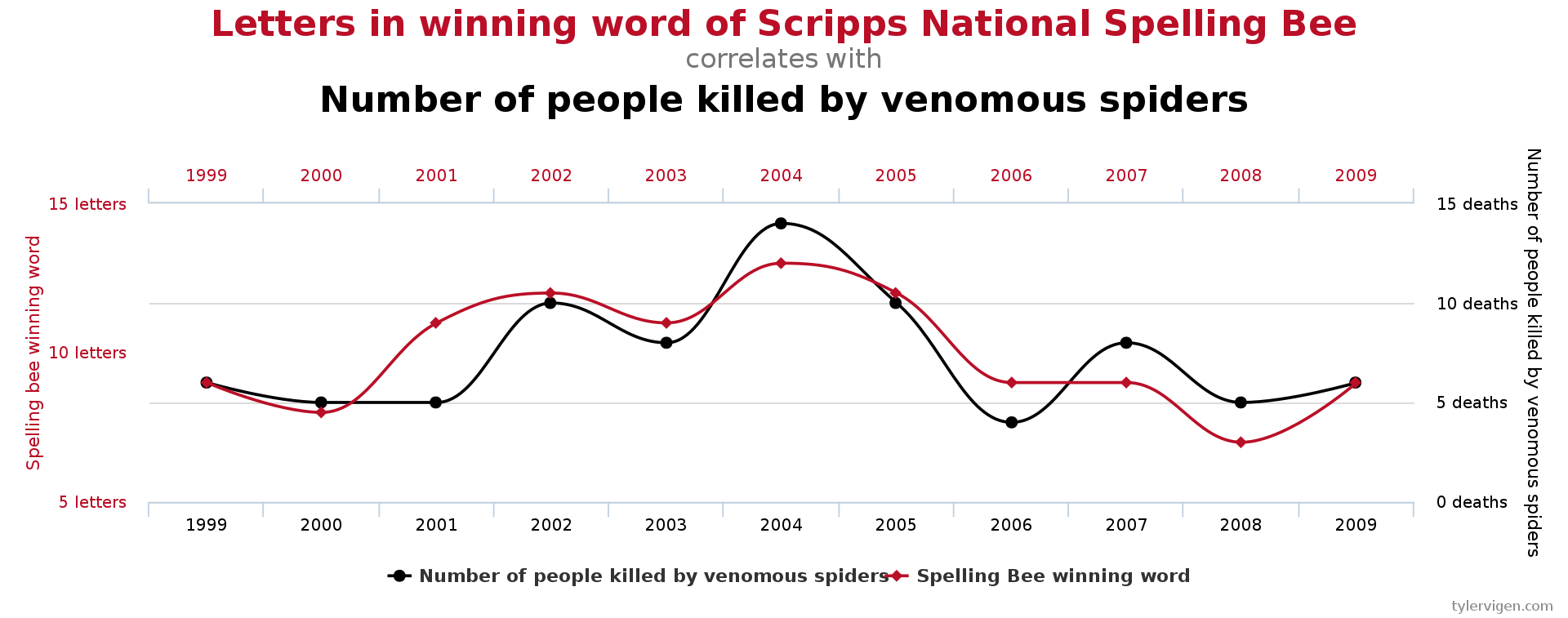

When R prints a regression summary, it adds stars to variables based on their \(p\)-values. Variables with \(p\)-values below 0.05 get one star, those with \(p\)-values below 0.01 get two stars, and those with \(p\)-values below 0.001 get three stars. A natural strategy for selecting significant variables is to choose those with one or more stars. However, the issue with this strategy is that even null variables (those with coefficients of zero) will sometimes have small \(p\)-values by chance (Figure 28.1). The more total variables we are testing, the more of them will have small \(p\)-values by chance. This is the multiplicity problem.

To quantify this issue, consider the case when all \(m\) variables under consideration are null. Then, the chance that any one of them has a \(p\)-value below 0.05 is 0.05. So, the expected number of variables with one or more stars is \(0.05m\). For example, if we have 100 variables, then we expect to see 5 variables with stars on average, even though none of the variables are actually relevant to the response! The growth of the quantity \(0.05m\) with \(m\) confirms that the multiplicity problem grows more severe as the number of hypotheses tested increases.

Another way of thinking about the multiplicity problem is in the context of selection bias. The process of scanning across all variables and selecting those with small \(p\)-values is a selection event. Once the selection event has occurred, one must consider the null distribution of a \(p\)-value conditionally on the fact that it was selected. Since the selection event favors small \(p\)-values, the null distribution of a \(p\)-value conditional on selection is no longer uniform; it becomes skewed toward zero. Interpreting \(p\)-values (and their accompanying stars) “at face value” is misleading because it ignores the crucial selection step. Other terms for this include “data snooping” and “p-hacking.”

The multiplicity problem is not limited to regression. In the next two sections, we develop some definitions to describe the multiplicity problem more formally and generally.

28.2 Global testing and multiple testing

Suppose we have \(m\) null hypotheses \(H_{01}, \dots, H_{0m}\). Let \(p_1, \dots, p_m\) be the corresponding \(p\)-values.

Definition 28.1 A \(p\)-value \(p_j\) for a null hypothesis \(H_{0j}\) is valid if \[ \mathbb{P}_{H_{0j}}[p_j \leq t] \leq t \quad \text{for all } t \in [0, 1]. \tag{28.1}\]

This definition covers the uniform distribution, as well as distributions that are stochastically larger than uniform. Distributions of the latter kind are often obtained from resampling-based tests, such as permutation tests. In the remainder of this chapter, we will assume that all \(p\)-values are valid.

Given a set of \(p\)-values, there are several inferential goals potentially of interest. These can be subdivided first into global testing and multiple testing.

Definition 28.2 A global testing procedure is a test of the global null hypothesis \[ H_0 \equiv \bigcap_{j = 1}^m H_{0j}. \] In other words, it is a function \(\phi: (p_1, \dots, p_m) \mapsto [0,1]\). A global test has level \(\alpha\) if it controls the Type-I error at this level: \[ \mathbb{E}_{H_0}[\phi(p_1, \dots, p_m)] \leq \alpha. \tag{28.2}\]

A global testing procedure determines whether any of the null hypotheses can be rejected. In regression modeling, a global test would be a test of the hypothesis \(H_0: \beta_1 = \cdots = \beta_m = 0\).

Definition 28.3 A multiple testing procedure is a mapping from the set of \(p\)-values to a set of hypotheses to reject: \[ \mathcal{M}: (p_1, \dots, p_m) \mapsto \hat{S} \subseteq \{1, \dots, m\}. \]

A multiple testing procedure determines which of the null hypotheses can be rejected. In regression modeling, a multiple testing procedure would be a method for selecting which variables have nonzero coefficients, the problem we discussed in the beginning of this section.

28.3 Multiple testing goals

Let us define \[ \mathcal{H}_0 \equiv \{j \in \{1, \dots, m\}: H_{0j} \text{ is true}\} \] and \[ \mathcal{H}_1 \equiv \{j \in \{1, \dots, m\}: H_{0j} \text{ is false}\}. \]

In other words, \(\mathcal{H}_0\) is the set of indices of the true null hypotheses, and \(\mathcal{H}_1\) is the set of indices of the false null hypotheses. There are two primary notions of Type-I error that multiple testing procedures seek to control: the family-wise error rate (FWER) and the false discovery rate (FDR).

28.3.1 Definitions of Type-I error rate and power

Definition 28.4 (Tukey, 1953) The family-wise error rate (FWER) of a multiple testing procedure \(\mathcal{M}: (p_1, \dots, p_m) \mapsto \hat{S}\) is the probability that it makes any false rejections: \[ \text{FWER}(\mathcal{M}) \equiv \mathbb{P}[\hat{S} \cap \mathcal{H}_0 \neq \varnothing]. \] A multiple testing procedure controls the FWER at level \(\alpha\) if \[ \text{FWER}(\mathcal{M}) \leq \alpha. \]

Definition 28.5 (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) The false discovery proportion (FDP) of a rejection set \(\hat{S}\) is the proportion of these rejections that are false: \[ \text{FDP}(\hat{S}) \equiv \frac{|\hat{S} \cap \mathcal{H}_0|}{|\hat{S}|}, \quad \text{where} \quad \frac{0}{0} \equiv 0. \] The false discovery rate (FDR) of a multiple testing procedure \(\mathcal{M}: (p_1, \dots, p_m) \mapsto \hat{S}\) is its expected false discovery proportion: \[ \text{FDR}(\mathcal{M}) \equiv \mathbb{E}[\text{FDP}(\hat{S})] = \mathbb{E}\left[\frac{|\hat{S} \cap \mathcal{H}_0|}{|\hat{S}|}\right]. \tag{28.3}\] A multiple testing procedure controls the FDR at level \(q\) if \[ \text{FDR}(\mathcal{M}) \leq q. \]

Regardless of what error rate a multiple testing procedure is intended to control, we would like it to have high power: \[ \text{power}(\mathcal{M}) \equiv \mathbb{E}\left[\frac{|\hat{S} \cap \mathcal{H}_1|}{|\mathcal{H}_1|}\right]. \]

28.3.2 Relationship between the FWER and FDR

Note that the FWER is a probability, while the FDR is an expected proportion. This distinction is highlighted by using the different symbols \(\alpha\) and \(q\) for the nominal FWER and FDR levels, respectively. The FWER is a more stringent error rate than the FDR, because it can only be low if no false discoveries are made most of the time; the FDR can be low if false discoveries are a small proportion of the total number of discoveries most of the time.

Proposition 28.1 For any multiple testing procedure \(\mathcal{M}\), we have \(\text{FDR}(\mathcal{M}) \leq \text{FWER}(\mathcal{M})\). Therefore, a multiple testing procedure controlling the FWER at level \(\alpha\) also controls the FDR at level \(\alpha\).

Proof. \[ \text{FDR} \equiv \mathbb{E}\left[\frac{|\hat{S} \cap \mathcal{H}_0|}{|\hat{S}|}\right] \leq \mathbb{E}\left[1(|\hat{S} \cap \mathcal{H}_0| > 0)\right] \equiv \text{FWER}. \]

The FWER was the error rate of choice in the 20th century, when limitations on data collection permitted only small handfuls of hypotheses to be tested. In the 21st century, the internet and other new technologies permitted much larger-scale collection of data, leading to much larger sets of hypotheses being tested (e.g., tens of thousands). In this context, the less stringent FDR rate became more popular. In many cases, an initial large-scale FDR-controlling procedure is viewed as an exploratory analysis, whose goal is to nominate a smaller number of hypotheses for confirmation with follow-up experiments. The purpose of controlling the FDR in this context is to limit resources wasted on following up false leads.